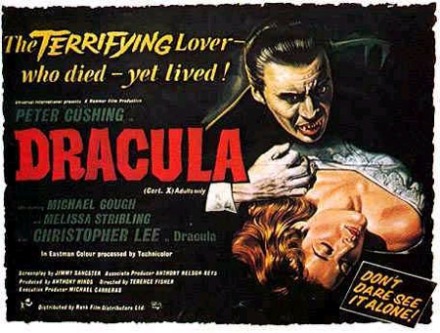

Not exactly seasonal subject matter, I know, but here’s the third in our series analyzing the enduring popularity of certain types of ghastly figures and horror stories (Zombies and Human Sacrifice have been covered in parts 1 and 2.)

So many versions and modifications to the mythology have arisen even since Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) that it would be counterproductive to survey their evolution here—and we are really interested in the archetypal fascination we all have with these figures of the night, anyway, and not their various historical guises.

Perhaps the best way to proceed would be to look beneath the common, classical “rules” about vamps, in order to uncover a theory that accounts for them. It is vital not to ignore the basic truth that even the most powerful vampires are extremely limited, or bound, by inviolable tenets. Writers who ignore these–in order to be “new”– are merely exhibiting a failure to comprehend why they became indispensable to the mythology to begin with. They are seven:

- “Vamps” are, almost by definition, sexual: we may as well begin on a compelling note. Animalistically sexual: nocturnal, sucking blood through canine teeth, and hypnotic if not actually attractive. The pop culture’s recent insistence on physical prettiness for both male and female nosferatu is not only redundant, but deceptive, and akin to confusing rape as a sexual crime versus its reality as a crime of violence. Remember that the victim is often killed, either immediately or over a succession of feedings.

- Vampires cannot withstand direct sunlight or mirrors, and cast no shadows or reflections. This would seem to suggest more than a hint of unreality about the creatures. But how can an illusion harm you?

- Certain vampires can morph into other forms: bats, mist, rats. Even in human form, they possess supernatural strength and are impervious to many kinds of harm.

- Vampires cannot enter a private dwelling unless invited in by the human inhabitant. The philosophical implication here is that only an act of free will can entangle one with a vampire, despite the seemingly contrary myth of hypnotic abilities or “glamoring” as a vampiric power (the two are not really mutually exclusive, and the paradox is resolved with the qualification that only individuals of weak will succumb to mesmerism.)

- Vampires must rest during the day, often in contact with the Earth or in a coffin (superficially suggesting another connection to Death; however classical mythology contains many chthonic beings associated with life—the Greek gods of the harvest, Demeter and Dionysus, for example).

- Vampires are immortal, or, alternatively, no longer alive—in either case, immune from further debilitating effects of aging, “frozen” at the age in which they perished from human form. Curiously, this also seems to manifest itself as an eternal adolescence, an inability to mature (in spite of many decades or centuries of experience and memories.) They can be destroyed, in certain ways: wooden stake to the heart, consumption by fire, and cutting off of the head are most commonly agreed upon.

- Vampires have no power over sacred Christian objects: crosses and crucifixes, holy water, recitations from or direct contact with the Bible. This invokes the often-made claim that a vampire is a human being divested of a soul.

In part 2 of this article, I will argue that these rules, far from being excessively imaginative or arbitrary, can all be resolved into a consistent and logical system, by an interrogation into the true nature of a vampire: Do they exist, or not? And if so, what are they, really?