by Shawn St.Jean

Commenting to the press on the assassination of President John Kennedy in late 1962, Malcolm X cold-bloodedly called the event a case of “the chickens coming home to roost.” Many would have preferred something a little more mournful and respectful. But over the years, I’ve come to see that this was what the occasion called for, amidst what X later clarified as “a climate of hate.” Because when you sow violence abroad and at home, as America does, it should be no shock when you, in turn, reap it.

These were among my reflections when, twenty years ago, I stood outside Columbine High School on a hot August day. I happened to be in the Littleton area, and I meant to visit whatever memorial had been erected to the thirteen shooting victims from 1999. Instead, I found a lonely building locked up tight for summer, surrounded by dried, pale grass of the drought season, and not a single living soul. Perhaps, I thought, there’s a plaque inside—for we dare not forget—and so I was alone with my thoughts.

Nearly ten years earlier than that, when I eneterd the graduate program at Kent State University (early 1990s,) I naturally assumed this would be the prevailing wind there, concerning the shootings of thirteen students there ( four deaths) in 1970, during a Vietnam War protest. To some extent, it was—though there are many there who opined “Let it go!” Which is a tribute, in one way, to a country where free speech is among the human rights guaranteed by our Constitution. At least, when stupidity gets voiced, we know what we’re up against.

Because there are a great many whose love for their own guns and 10,000 rounds of personally stockpiled ammo mean more than the lives of a few hundred Americans, each year. And there are others whose love for money, or privilege, or power, or plain old violence are greater. And there are many who just don’t give a shit.

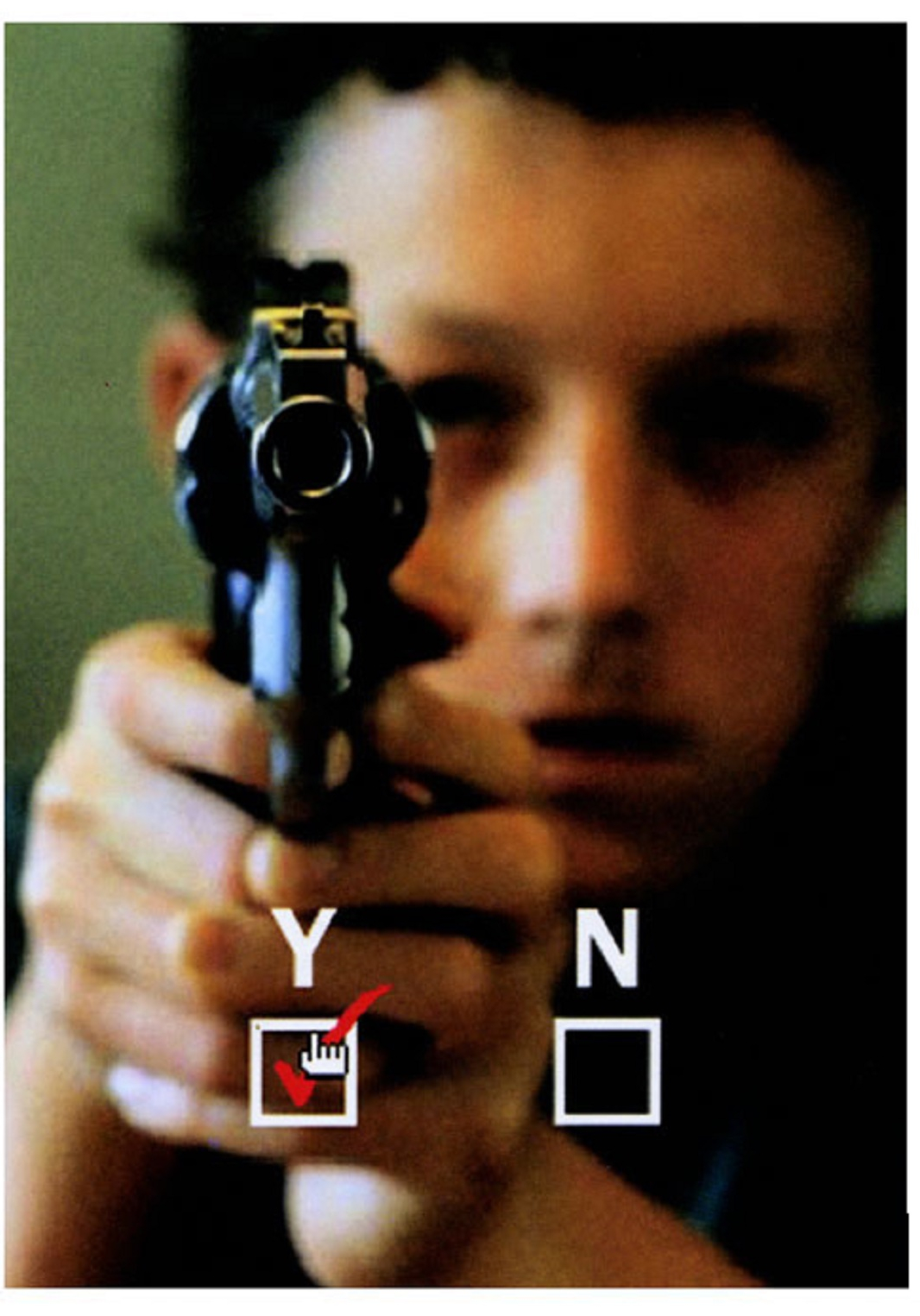

Ask yourself, among everything we’ve been conjured to forget: How often does a rich guy like Kennedy get hit? Ask most poor people when they think the mass shootings, like the one at Michigan State University this past Monday, will cease—or at least, subside, because the federal government finally did something about it. (Bear in mind, this latest site of violence is not exactly a seat of the ivy league. It’s where those who are willing to sign tens of thousands of dollars in student loans go.) The answer is not too difficult: When some wealthy senator or congressman’s child is killed, that’s when. THEN you’ll see the real tears, hear the speeches, that mean action. Then you’ll see bills with teeth, that threaten to take assault weapons off the streets. But not before, sadly. Because despite the doleful addresses of the President and guardians of whatever building the latest incident occurred in, one truth rings as clear as a shot: Rich people, the vast majority of them—don’t really give a shit about poor people. Not in coal mines or railroad and bread lines, and modern toxic workplaces, not in natural disasters, not in other countries be they our so-called allies or enemies, not in Wal-mart or the public elementary schools, not in the U.S. military. Yeah, Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez aside, and a few others. Only most of them. They cry on their sleeves, and reach back and feel for their wallets.

The politicians will say it’s hard: an uphill battle, against the two-party, obstructionist system which has crippled our republic. It’s difficult even to figure out what the bill might say, in the face of the Constitutional guarantee to “keep and bear arms” by the citizenry. A nearly 250-year-old provision written by men who could no more conceive of the one-shot flintlock evolving into the AR-15, than you or I believe in instantaneous transport to Mars. And change is built into that document—because they were wise enough to know, we’d need it.

Of course, it’s hard. That’s their job. To sit in that room and argue, debate the possibilities, cut deals–whatever it takes to protect the country. There’s never been much of a hard time rescinding our other rights under the Patriot Act, or dropping bombs on other nations, or authorizing HALF of the latest mammoth Omnibus appropriation for weapons of war. Violence is easy, apparently. Try Peace. Try doing your jobs.

So, in the spirit of Malcolm X, I say, let that unlucky Rich Person’s son or daughter bleed to death of a gunshot wound, as soon as possible—the sooner, the better. That poor soul will not have died in vain. It’s no longer a time for short-lived remembrance and long-term amnesia, or reflection, or mourning and healing, or holding hands and bowing our heads for the national anthem and flags at half-mast, or even John Oliver’s editorials, or especially more bullshit condolence speeches. It’s a time for anger and perhaps counter-violence, of a sort. One hesitates to fight fire with fire—but when water evaporates, and the very ground beneath your feet burns, you gotta use something. We’re long overdue for action.

Lest anyone think I mean arm yourselves, arm teachers, hire more cops. . .NO. That’s stupid. Guns are the problem. You think that moron could have attempted to murder eight people yesterday, with a deer rifle? So no, I don’t mean ban firearms either. Equally stupid. Any thinking person knows there’s a middle ground there, somewhere, and at this point, it’s clear: pretending otherwise is contributing to the next set of murders.

People always hesitate at where to start. That IS the hardest part of any action. So I’ll offer my suggestion—not in expectation that people will take it, but as a challenge to consider where YOU will start.

We’ve already got politicians declaring to run in the next big election. Fine. And we know we’re going to hear a lot of promises. Fine. Challenge them. Offer them a show of the kind of violence they understand. Because they need the incentive. Offer to end their career for them: What are you doing to end gun violence? I want to see your ACTION, Mr or Ms President or Whatever Wannabe, before the election; NOT promises, ACTION—on gun control. And if I don’t see it, you will not get my vote. And I’ll make sure I use all the power of the internet to persuade people that you should not get their vote, either.

This kind of action sure beats the alternative. Either way, we—the poor—are in the crosshairs. Not them. Us.

Here lies a subject that it would take a large book to survey, let alone a blog post. So I’ll necessarily confine myself to one small phenomenon, far more limited even than the katabasis (mythological journey into the Underworld): the anthropomorphic figure of Death (that is, Death given a human shape and characteristics.) Not all mythologies do this. For example, in a Boethian universe (one in which evil does not exist as a force, but rather as an absence,) Death is not considered evil, but more often incarnates as the end of a cycle–like winter ends our calendar year. If you’re a Buddhist, it might not even signal an ending–but the beginning of a next life, during one’s journey in Samsara (the cycle of reincarnations, culminating hopefully in Nirvana).

Here lies a subject that it would take a large book to survey, let alone a blog post. So I’ll necessarily confine myself to one small phenomenon, far more limited even than the katabasis (mythological journey into the Underworld): the anthropomorphic figure of Death (that is, Death given a human shape and characteristics.) Not all mythologies do this. For example, in a Boethian universe (one in which evil does not exist as a force, but rather as an absence,) Death is not considered evil, but more often incarnates as the end of a cycle–like winter ends our calendar year. If you’re a Buddhist, it might not even signal an ending–but the beginning of a next life, during one’s journey in Samsara (the cycle of reincarnations, culminating hopefully in Nirvana).